Shields Tavern Archaeological Report, Block 9 Building 26BOriginally entitled: "Archaeological Investigations of the Shields Tavern Site, Williamsburg, Virginia"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1626

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE SHIELDS TAVERN SITE, WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

Principal Investigator:

Dr. Marley R. Brown III

Maps and Graphics by:

Kimberly A. Wagner, Tamera A. Mams,

and Virginia C. Brown

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | |

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | ix |

| LIST OF FIGURES | xi |

| LIST OF TABLES | xv |

| PHOTO AND ILLUSTRATION CREDITS | xvii |

| CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| CHAPTER 2. PROPERTY DESCRIPTION | 5 |

| Historical Background | 7 |

| Immediate Surroundings | 8 |

| CHAPTER 3. THE ROLE OF TAVERNS IN COLONIAL TOWNS | 15 |

| Drinking, Lodging, and Gambling | 17 |

| Tavern Landscapes | 19 |

| Food Service | 20 |

| CHAPTER 4. PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGY | 23 |

| CHAPTER 5. METHODS | 29 |

| Field Methods | 29 |

| Laboratory Methods | 35 |

| Zooarchaeological Laboratory Methods | 36 |

| Documentary Research | 39 |

| Report Format | 39 |

| CHAPTER 6. THE PRE-TAVERN PERIOD (1633-1708) | 41 |

| Documentary and Archaeological Data | 41 |

| Artifactual and Zooarchaeological Evidence | 44 |

| CHAPTER 7. THE EARLY TAVERN PERIOD (1708-1738) | 45 |

| Documentary Information | 45 |

| Archaeological Data | 54 |

| Spatial Patterning | 63 |

| Artifactual Information | 70 |

| Zooarchaeological Data | 84 |

| CHAPTER 8. THE LATE TAVERN PERIOD (1738-1751) | 91 |

| Documentary Information | 91 |

| Archaeological Data | 97 |

| Spatial Patterning | 113 |

| Artifactual Information | 114 |

| Zooarchaeological Data | 122 |

| CHAPTER 9. THE POST-TAVERN PERIOD (1751-1800) | 133 |

| Documentary Information | 133 |

| Archaeological Data | 137 |

| Artifactual Information | 152 |

| Zooarchaeological Data | 159 |

| viii | |

| CHAPTER 10. THE NINETEENTH CENTURY AND LATER | 167 |

| Documentary Information | 167 |

| Archaeological Data | 169 |

| Artifactual and Zooarchaeological Data | 171 |

| CHAPTER 11. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY | 173 |

| Landscape Modification | 173 |

| Occupational Specialization and the Rise of Neighborhoods | 177 |

| Public and Private Foodways | 179 |

| Tavern Functions, Expenditure Patterns, and Personal Possessions | 183 |

| Recommendations for Future Research: The Tavern Assemblage | 188 |

| Recommendations for Future Research: The Draper Assemblages | 188 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 191 |

| APPENDIX 1. THE PROBATE INVENTORIES OF JEAN MAROT AND JAMES SHIELDS II | 201 |

| APPENDIX 2. DESCRIPTIVE CATALOG OF ILLUSTRATED ARTIFACTS | 209 |

| APPENDIX 3. SELECTED FOOD PURCHASES BY TAVERN KEEPERS IN THE JAMES BRAY AND CARTER BURWELL ACCOUNT BOOKS | 221 |

| APPENDIX 4. DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE FOR THE DIET OF AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY GENTLEMAN: WILLIAM BYRD II OF WESTOVER | 227 |

| APPENDIX 5. ARTIFACTUAL DATA | 233 |

| APPENDIX 6. FAUNAL DATA | 241 |

Acknowledgments

In a project of this sort, one incurs debts of gratitude almost daily, from those colleagues who provide important interpretive suggestions to those who provide more mundane but essential physical assistance. Because even controlled archaeological excavation at times resembles mass chaos, the sheer scope of the work and volume of information generated demands a variety of support services and a high degree of cooperation. It is not likely that we will remember all the people that helped in one way or another, but they can be assured that all contributions were sincerely appreciated.

Excavations were performed under severe time pressure and in a variety of unpleasant conditions. Principal thanks, therefore, must go to the talented field crew: Mark Canada, John Cross, Wyn Dudley, Barbara Heath, Jeff Holland, Barbara Larkin, Nicola Longford, Meredith Moodey, Monica Patten, Melissa Payne, Martin Reinbold, Charles Thomas, Lucie Vinciguerra, and Mary Zylowsld. Much of the artifact processing was performed by laboratory technicians Leslie McFaden and Sue Alexandrowicz, and some faunal processing by zooarchaeological assistant Eric Ackermann.

Like the fieldwork itself production of this report is a cooperative enterprise. Project archaeologist Thomas F. Higgins III and crew chief David F. Muraca directed the actual excavations, and produced the main descriptive portions of the text. Artifact and faunal analyses were added by laboratory technicians S. Kathleen Pepper and Roni H. Polk, while collections supervisor William E. Pittman and staff zooarchaeologist Joanne Bowen Gaynor oversaw these analyses and added important interpretive contributions. The artifact sections were reviewed and strengthened by research fellow Ann Smart Martin and senior laboratory analyst George Miller. The extraordinary artifact illustrations were produced by Kimberly Wagner and Tamera Mams. Ms. Mams also provided the photographic services, as well as overseeing report layout. Maps were generated on microcomputer using AutoCAD™ drawing software, from original drawings by Kimberly Wagner and Virginia C. Brown.

Marley R. Brown III, Director of the Department of Archaeological Research, provided basic guidance regarding the direction of analysis, as well as overseeing the fieldwork itself. Other members of the Department, including Patricia Samford, Andrew Edwards, and Robert Hunter, supplied needed assistance on many occasions.

Several Colonial Williamsburg officials also aided us greatly. Peter A.G. Brown, Vice-President for Programs and Exhibitions, gave us the time and money to get the work completed. Senior Vice-President Robert C. Birney and Vice-President for Research Cary Carson provided support and logistical assistance.

A number of colleagues have reviewed this manuscript and/or provided their interpretations of various features or objects. We would like to particularly thank Patricia A. Gibbs of the Department of Historical Research; Mark R. Wenger and Edward Chappell x of the Department of Architectural Research; Orlando Ridout, formerly of the Department of Architectural Research; retired Foundation Archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume; curators John C. Austin and Jay Gaynor of the Department of Collections; and coach driver Richard Powell, coach driver Kay Williams, blacksmith Peter Ross, blacksmith Dave Harvey, and cooper Lew LeCompte of the Department of Historic Trades. We are also grateful for the help provided by the staff of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, particularly Mary Keeling, Susan Berg, John Ingram, Jim Garrett, and Suzanne Brown.

G.J.B.

LIST OF FIGURES

| Page | |

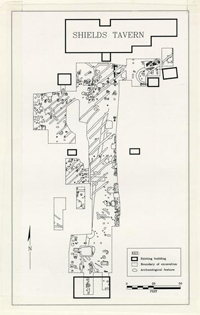

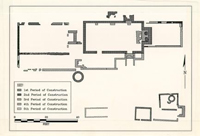

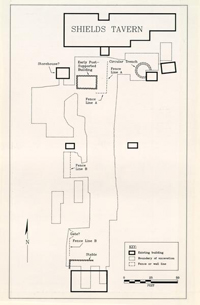

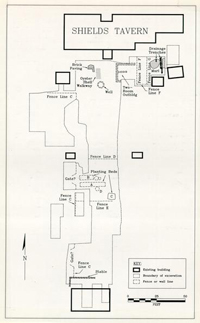

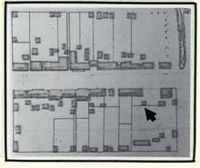

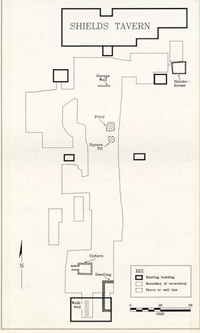

| Frontispiece. Composite map of excavated features | ii |

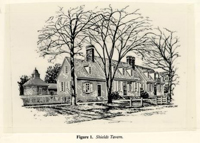

| Figure 1. Shields Tavern | 5 |

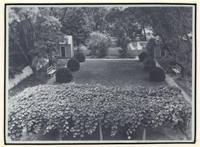

| Figure 2. Back yard prior to excavation | 6 |

| Figure 3. Proposed restoration plan for back yard | 6 |

| Figure 4. Location of Shields Tavern in eighteenth-century Williamsburg | 7 |

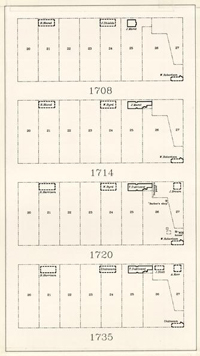

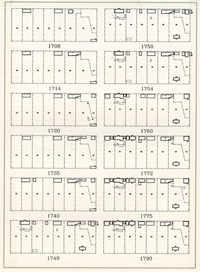

| Figure 5.Buildings on Block 9 in 1708, 1714, 1720, and 1735 | 9 |

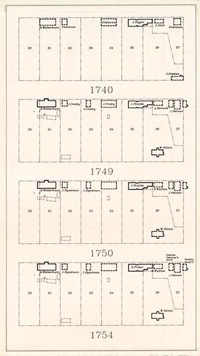

| Figure 6.Buildings on Block 9 in 1740, 1749, 1750, and 1754 | 11 |

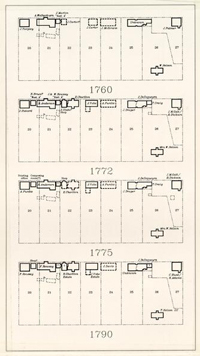

| Figure 7.Buildings on Block 9 in 1760, 1772, 1775, and 1790 | 13 |

| Figure 8.Tavern life | 18 |

| Figure 9.Archaeological features discovered by James M. Knight in 1951-52 | 23 |

| Figure 10.Tavern foundations | 24 |

| Figure 11.Tavern foundations | 25 |

| Figure 12.Outbuilding foundations | 26 |

| Figure 13.Archaeological features discovered on the Coke Office lot in 1957-58 | 27 |

| Figure 14.Excavation grid | 30 |

| Figure 15. Initial excavation units | 31 |

| Figure 16.Sample context record | 33 |

| Figure 17.Harris matrix diagram | 34 |

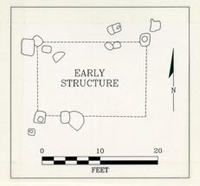

| Figure 18.Pre-Tavern period archaeological features | 42 |

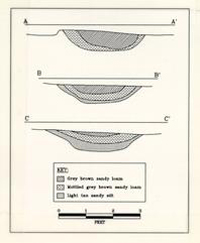

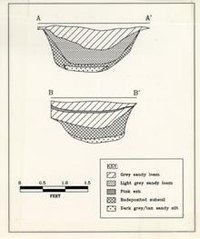

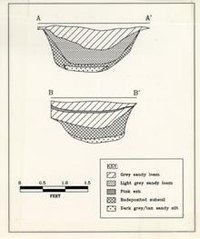

| Figure 19.Profile of boundary ditch | 43 |

| Figure 20.Reconstruction of Middle Plantation showing location of boundary ditch | 44 |

| Figure 21.Early Tavern-period archaeological features | 55 |

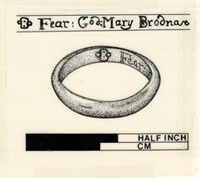

| Figure 22.Gold child's ring inscribed "Fear God Mary Brodnax" | 56 |

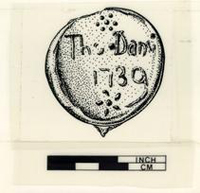

| Figure 23.Wine bottle seal embossed "Th Dan ... 1739" | 56 |

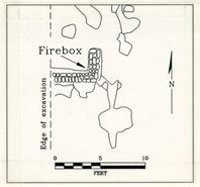

| Figure 24.Circular trench | 57 |

| Figure 25.Profile of circular trench | 57 |

| Figure 26.Cider press in Diderot's Encyclopedia | 58 |

| Figure 27."Pit Ticket: The Cockpit" by William Hogarth, 1579 | 60 |

| Figure 28.Early post-supported building | 61 |

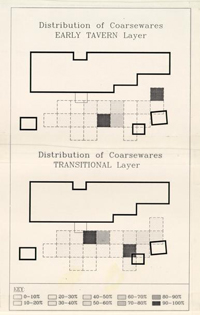

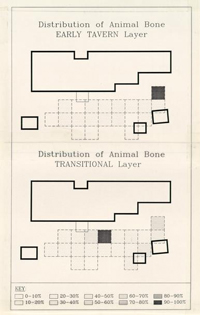

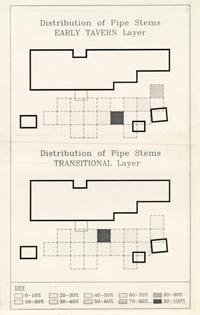

| Figure 29.Distribution of coarsewares | 65 |

| Figure 30.Distribution of animal bone | 66 |

| Figure 31.Distribution of pipe stems | 67 |

| Figure 32.Distribution of delftware | 68 |

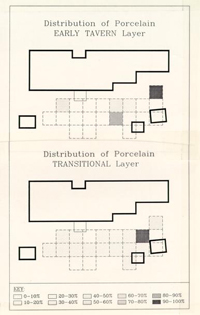

| Figure 33.Distribution of porcelain | 69 |

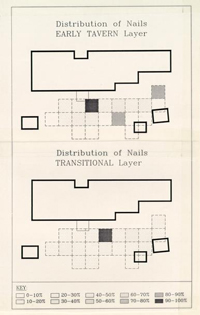

| Figure 34.Distribution of nails | 71 |

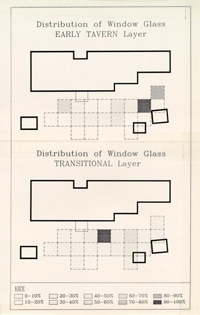

| Figure 35.Distribution of window glass | 72 |

| Figure 36.Distribution of stonewares | 73 |

| xii | |

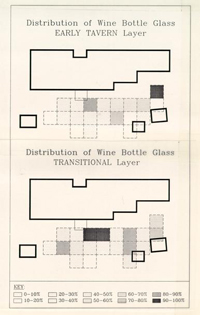

| Figure 37. Distribution of wine bottle glass | 74 |

| Figure 38.English delftware tea bowl | 77 |

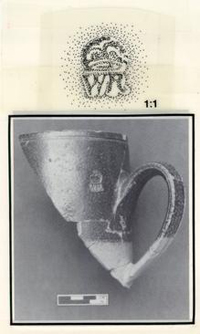

| Figure 39.Fulham tankard with impressed "WR" | 78 |

| Figure 40.Shaw salt-glazed stoneware tankard | 79 |

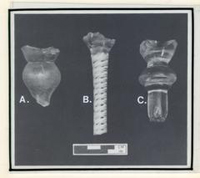

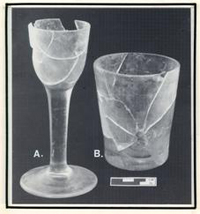

| Figure 41.Stemmed glass tableware | 83 |

| Figure 42.Harness boss | 83 |

| Figure 43.Inscribed silver seal | 83 |

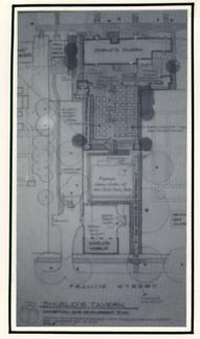

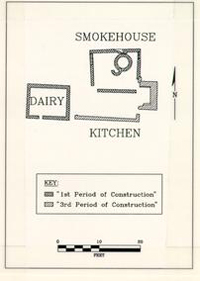

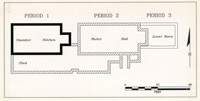

| Figure 44.Architectural plan of Shields Tavern in 1750 | 93 |

| Figure 45.Late Tavern period archaeological features | 98 |

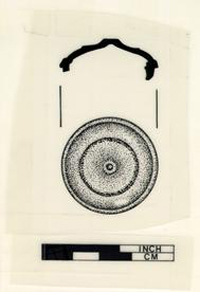

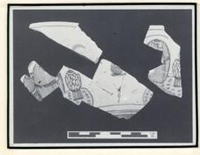

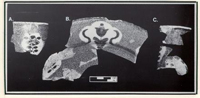

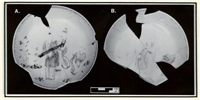

| Figure 46.Manganese powdered ground delftware plate and cups | 99 |

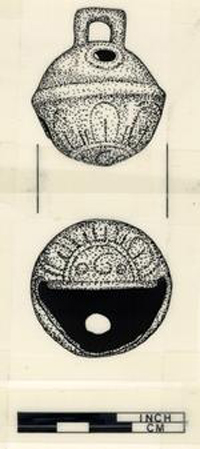

| Figure 47.Rumbler bell | 100 |

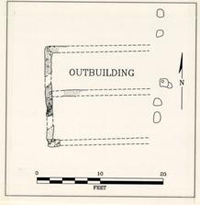

| Figure 48.Two-room outbuilding | 102 |

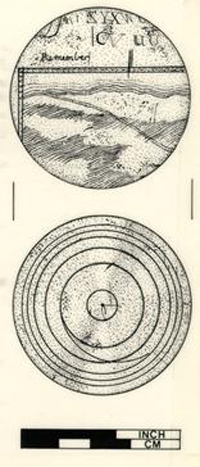

| Figure 49.Copper alloy disk cut from engraving plate | 105 |

| Figure 50.Outbuilding foundations discovered in 1951-52 | 109 |

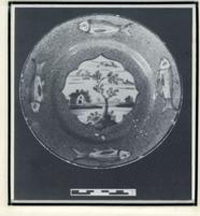

| Figure 51.Polychrome delftware punch bowl | 118 |

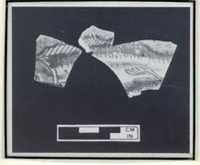

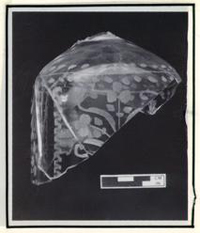

| Figure 52.Fish motif manganese powdered ground delftware plate | 119 |

| Figure 53.Stemmed glass tableware | 122 |

| Figure 54.Post-Tavern-period archaeological features | 138 |

| Figure 55.Forge and abandoned well | 139 |

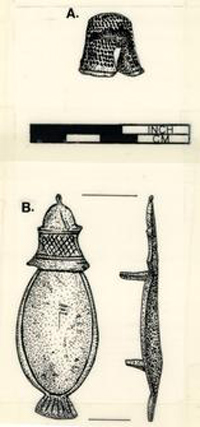

| Figure 56.Thimble and thumbplate discovered in anvil stump | 140 |

| Figure 57.Area of Draper's original forge | 141 |

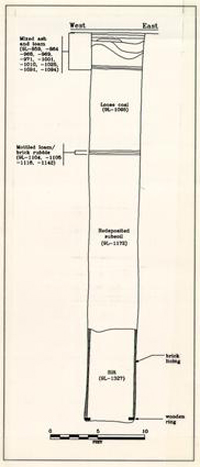

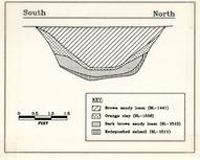

| Figure 58.Profile of well | 143 |

| Figure 59.Wooden tub found in lowest level of well | 144 |

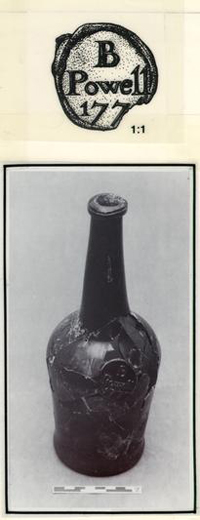

| Figure 60.Bottle with seal embossed "B. Powell 1774" | 144 |

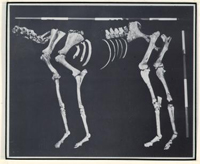

| Figure 61.Horse burial in situ | 147 |

| Figure 62.Profile of horse burial pit | 147 |

| Figure 63.Re-articulated remains found in horse burial pit | 148 |

| Figure 64.Frenchman's Map (1782), showing outbuilding in east yard | 149 |

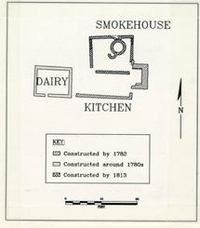

| Figure 65.Outbuildings in east yard | 150 |

| Figure 66.Matching overglaze polychrome porcelain saucers | 154 |

| Figure 67.Nottingham stoneware mug | 154 |

| Figure 68.Leaded wine glass and tumbler | 155 |

| Figure 69.Copper-wheel engraved glass decanter | 155 |

| Figure 70.Creamware feather-edged plate and undecorated tea bowl | 156 |

| Figure 71.Red-bodied slipware bowl | 156 |

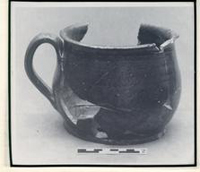

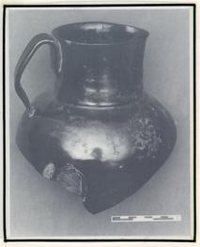

| Figure 72.Jackfield-type pitcher | 156 |

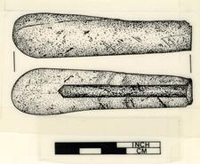

| Figure 73.Antler cutlery handle | 157 |

| Figure 74.Case bottle | 157 |

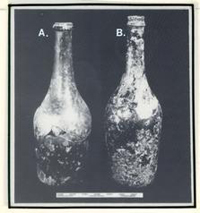

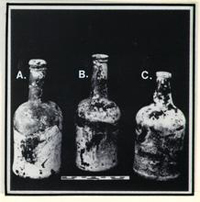

| Figure 75.English beer quarts | 157 |

| Figure 76.French champagne bottles | 158 |

| Figure 77.Chamber pot | 158 |

| xiii | |

| Figure 78. Bone button blanks | 158 |

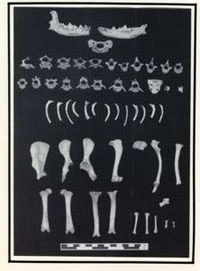

| Figure 79.Immature dog found in well | 162 |

| Figure 80.1921 Sanborn map | 168 |

| Figure 81.1929 Sanborn map | 168 |

| Figure 82.1933 Sanborn map | 169 |

| Figure 83.Nineteenth- and twentieth-century archaeological features | 170 |

| Figure 84.Block 9 in the eighteenth century | 176 |

| Figure 85.Dietary patterns in the William Byrd diaries | 181 |

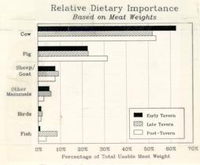

| Figure 86.Relative dietary contribution based on faunal analysis | 182 |

| Figure 87.Age distributions based on epiphyseal fusion | 184 |

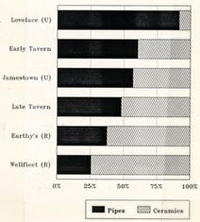

| Figure 88.Comparison of pipes vs. ceramics from tavern sites | 185 |

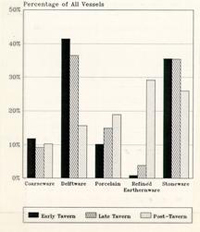

| Figure 89.Distribution of vessel forms | 186 |

| Figure 90.Distribution of ware types | 187 |

| Figure 91.Fish motif manganese powdered ground delftware plate used in modern tavern | 188 |

| Figure 92.Element distributions for domestic cow (Bos taurus) and domestic pig (Sus scrofa) | 252 |

| Figure 93.Element distributions for domestic sheep/goat (Ovis aries/Capra hircus) and chicken (Gallus gallus) | 253 |

LIST OF TABLES

| Page | |

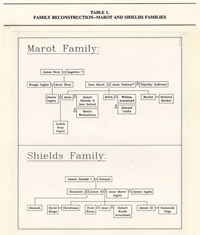

| Table 1. Family reconstruction--Marot and Shields families | 52 |

| Table 2. Distribution of vessel forms--Early Tavern period | 76 |

| Table 3. Distribution of ware types--Early Tavern period | 76 |

| Table 4. Animals represented in the Early Tavern faunal assemblage | 84 |

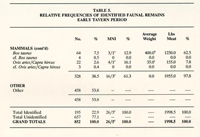

| Table 5. Relative frequencies of identified faunal remains-- Early Tavern period | 88 |

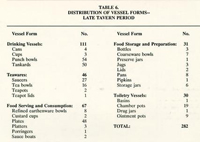

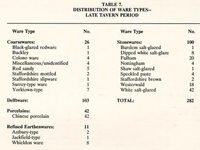

| Table 6. Distribution of vessel forms--Late Tavern period | 114 |

| Table 7. Distribution of ware types--Late Tavern period | 115 |

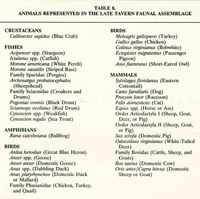

| Table 8. Animals represented in the Late Tavern faunal assemblage | 123 |

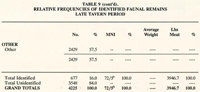

| Table 9. Relative frequencies of identified faunal remains-- Late Tavern period | 130 |

| Table 10. Identifiable objects recovered from the well | 145 |

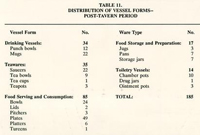

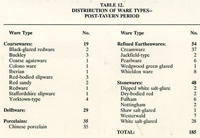

| Table 11. Distribution of vessel forms--Post-Tavern period | 153 |

| Table 12. Distribution of ware types--Post-Tavern period | 153 |

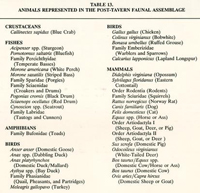

| Table 13. Animals represented in the Post-Tavern faunal assemblage | 160 |

| Table 14. Relative frequencies of identified faunal remains-- Post Tavern period | 164 |

| Table 15. Excerpts from the Carter Burwell account book, 1738-1755 | 223 |

| Table 16. Excerpts from the James Bray account book, 1736-1746 | 226 |

| Table 17.References in William Byrd II's secret diaries to meals eaten at Marot's Ordinary, 1710-1712 | 229 |

| Table 18.References in William Byrd II's secret diaries to meals eaten at Wetherburn's Tavern, 1739-1741 | 230 |

| Table 19. Ceramic vessels--Early Tavern period | 235 |

| Table 20. Ceramic vessels--Late Tavern period | 236 |

| Table 21. Ceramic vessels--Post-Tavern period | 238 |

| Table 22. Sherd counts used in spatial distribution diagrams | 240 |

| Table 23. Epiphyseal fusion data | 243 |

PHOTO AND ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

| Figure | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Drawing used in Colonial Williamsburg Official Guidebook, 1984. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg. Courtesy of Audio Visual Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| 3 | Designed by Kent Brinkley, Dept. of Architecture and Engineering, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| 4 | Based on "College Map," circa 1790. Photostat on file, Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| 8 | Print, "Slow Time," made in England, ca 1750-1775. Courtesy of Audio-Visual Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| 10 | C.W. Photo 52-T-651. Courtesy of Audio-Visual Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| 11 | C.W. Photo 52-T-662. Courtesy of Audio-Visual Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| 12 | C.W. Photo 52-T-657. Courtesy of Audio-Visual Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| 20 | Base map from James M. Knight, 1942, "Old Road Through Middle Plantation." Map on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg. |

| 26 | Charles Coulston Gillispie, 1959, A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry. Manufacturing and the Technical Arts in Plates, selected from L'Encyclopedie... Dover Publications, New York. |

| 27 | Sean Shesgreen, 1973, Engravings by Hogarth. Dover Publications, New York. |

| 64 | Anonymous, 1782, Plan de la ville et environs de Williamsburg en Virginie, 1782. Photostat on file, Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg. |

| 80 | Sanborn Map Company, New York. 81 Sanborn Map Company, New York. |

| 82 | Sanborn Map Company, New York. |

| 88 | Comparative data from Diana DiZ. Rockman and Nan Rothschild, 1984, City Tavern, Country Tavern: An Analysis of Four Colonial Sites. Historical Archaeology 17:112-121. |

| 91 | Courtesy of Shields Tavern. |

Chapter 1: Introduction

Taverns were an important part of eighteenth-century towns, as much for their social role as their economic one. In 1744, Pennsylvania traveller William Black observed:

I do assure you that it was the Pleasures of Conversation, more than of the Glass, that Induc'd me [to the tavern]: I observed that in such Company, I could Learn More of the Constitution of the Place, their trade, and manner of living, in one hour, than a Week's Observation Sauntering up and down the City could produce, besides numberless other Advantages which is to be gather'd from the conversation of a Polite company, which brings many helps to the understanding of a Person, who otherwise has his sight limited to the length of his Nose... (Brock 1877:405, cited in Rice 1983).

Yet relatively few taverns have been archaeologically investigated in depth, and even fewer have provided a combination of rich documentary and archaeological data which can be compared and contrasted. One such place, fortunately, was discovered in the course of relatively routine salvage archaeology in 1985.

The 1985-86 archaeological investigation of the Shields Tavern property was prompted by the planned construction of an underground kitchen, twenty feet below modern grade, and the conversion of the reconstructed building into the fourth operating tavern within the Colonial Williamsburg Historic Area. At the time it was known that the property had been an important one during the eighteenth century, and despite significant disturbances it was felt that valuable archaeological information could be gathered from a reexcavation of the area. This information would, it was hoped, provide evidence of the daily lives of the tavern keepers, their families, and their clients, which would later be used in the reinterpretation and refurbishment of the building.

Because very little could be learned from the early archaeological work in the 1950s, which was aimed primarily at the reconstruction of the main structure and principal outbuildings, intensive new archaeological excavations were conducted by Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research, formerly the Office of Archaeological Excavation, under the direction of Dr. Marley R. Brown III. These excavations provided not only a chance to recover evidence of tavern life, but also an opportunity to explore the changes that took place on a heavily-used property in one of the most important commercial areas of the eighteenth-century town.

The excavations were performed between August 13, 1985 and July 1, 1986, in a 220-by-130-foot area behind the existing tavern building. The crew consisted of five to ten excavators, under the supervision of project archaeologist Thomas F. Higgins III and crew chief David F. Muraca. Artifact processing was supervised by laboratory technician S. Kathleen Pepper, and animal bone processing by laboratory technician Roni H. Polk. Much of the historical background work was performed by staff archaeologist Gregory J. Brown, who also undertook the final 2 editing and interpretation upon the departure of Mr. Higgins.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Despite the salvage nature of the project, which imposed significant limitations, it was possible to formulate a detailed and specific research design. Although the design was not explicitly stated in writing, as it developed the project became an investigation of four of the Department's particular research interests: (1) urbanization and the effect of urbanization on the landscape; (2) occupational specialization and neighborhood formation; (3) public and private foodways; and (4) expenditure patterns and consumer behavior. It was specific questions in these areas, along with the need to gather information that could be used in reconstructing the landscape of the yard, which determined the techniques and strategies that were employed.

The first of these research problems is obviously important. The increasing urbanization of Williamsburg throughout the eighteenth century is reflected quite dramatically in the landscape, and these landscape alterations can be interpreted effectively using archaeology (e.g., see Kelso 1984). The location and size of garden beds, the position and architectural form of outbuildings, and even the presence of relatively minor landscape features such as drainage ditches can reveal much about how a property was actually used. But changes in the landscape were not simply physical alterations; they were also the result of changes in perception and world view (Leone 1984). It is often argued, for instance, that the appearance of the so-called "Georgian order," with its strong bilateral symmetry and balance, can be seen archaeologically in the floor plans of new structures and the design of formal gardens (Deetz 1977).

Accepting the premise that material remains were manifestations of some sort of cultural design process, it is possible to see in the ground a window, though imperfect, into the changes taking place in the social and economic spheres. Many of these social and economic changes, of course, were reflections of the growth of the town itself.

Clearly, the ways in which the local landscape was modified depended largely upon social class and economic means. By controlling for these factors, it is possible to see particular strategies developed in response to growing urbanization and, indirectly, the shifts in social interaction, political power, and economic well-being that accompanied this process.

Continuous eighteenth-century activity on the Shields Tavern property resulted in a staggering number of features and occupation layers. Controlled excavation allowed the recovery of essential data that could be used in evaluating and interpreting even the most subtle changes in what was after all an ever-changing cultural landscape. The Shields Tavern yard, for example, yielded distinct evidence of complex landscape alterations including fence lines, walkways, wells, garden beds, outbuildings, and forges. In addition, refuse concentrations associated with several features revealed discernible patterns of yard utilization associated with specific commercial activities.

3The strong archaeological and documentary records for the Shields Tavern property allow not only site-specific landscape reconstruction, but also the opportunity to pose research questions based on a neighborhood-wide perspective. Understanding what a tavern did in the context of its place within the town can reveal much about community interaction. Part of this interaction is particularistic--for example, the discovery of a child's lost gold ring in Marot's back yard which appears to indicate friendship between Marot's daughters and the daughter of goldsmith John Broadnax (see Chapter 7). Another part, however, rests on generalizations made on the basis of studying occupationally-diverse properties in different parts of town. The questions include how a tavern is like (or unlike) a store, a craftsman's home and workplace, or a so-called "urban plantation." They also include how a tavern in one part of town, serving one clientele, is like or unlike another tavern in a different part of town. These questions are necessarily difficult, since they involve comparisons with a wide range of other well-excavated properties. Nonetheless, descriptive data such as that gathered at Shields Tavern is one of the few ways that one can start, at least, to build up a relevant database.

Two other classes of data--faunal and artifactual--provide a means of studying foodways and consumer behavior. Foodways--the "whole interrelated system of food conceptualization, procurement, distribution, preservation, and consumption shared by all members of a particular group" (Anderson 1971:xl)--is studied most directly by looking at the animal bones and seeds that are the actual refuse of former meals. Zooarchaeology (the branch of archaeology that studies animal remains) has already made important contributions to an understanding of food; its relevance to colonial-period Chesapeake foodways, however, is only now becoming clear. One important aspect of a comprehensive study of Chesapeake foodways, which is now being planned (Gaynor et al. 1985), involves an understanding of the concept of "public" foodways--the commercial cookery of the taverns and boardinghouses.

The life of the tavern can be measured not only through what kinds of food was served, but also through the elegance and quality of the decor. A study of artifactual evidence can indicate the commercial behaviors that must have influenced how the tavern keeper's establishment was perceived by others, and even how he himself perceived it. Personal wealth was of course not the only factor which contributed to the makeup of the tavern's furnishings. Differences in expenditure patterns, however, can be glimpsed by comparing the stated wealth of the tavern keeper with the actual range of possessions revealed in the archaeological assemblages.

This type of study should be undertaken only with great care, realizing how little we really know about expenditure patterns in the eighteenth century in general. Temporal differences, moreover, must be taken into consideration. During the eighteenth century there was also a dramatic change in the public perception of non-essential goods. Lois Green Carr and Lorena Walsh's recent probate study indicates that, by the end of the seventeenth century: 4

The [Chesapeake] region's wealthiest men and women had not yet adopted an integrated lifestyle set off from that of other groups, but by 1700, nonetheless, they could be distinguished far more readily from others than in the 1660s. [The wealthiest estates] usually contained most of the available comforts or one or two luxuries--pictures, watches and clocks, large looking glasses, or window curtains for example and a few showed signs of taking up newer fashions such as a more widespread use of table knives and forks, the acquisition of a few pieces of imported furniture, and most consistently, increasingly larger quantities of elaborately wrought silver plate (1985:7).The trend continued for the next several decades, eventually reaching a point where:

the range of domestic props that gentlefolk found desirable had exploded. Matched china place settings; mahogany chairs, tables, buffets, and bookcases, specialized beverage glasses and serving dishes, an impressive array of kitchen gadgetry, garniture; candelabra; prints; tea and coffee services--to name a few--began to fill up larger, more formal dwellings that now boasted separate drawing and dining rooms. Social spaces became divorced from workplaces, storerooms, and sleeping quarters, and each area was furnished with increasingly specialized equipment appropriate to the activities, formal or informal, there pursued (Walsh 1983:111).

Thus, while acknowledging that assemblages from different time periods will naturally have different characteristics, it is felt that there is some value in comparing the artifact assemblages generated during the various phases of site occupation. Of specific interest, and perhaps most revealing, is the analysis of ceramics and glass from the tavern-period layers and features. Clearly, the comparative study of assemblages from the earlier and later tavern-period contexts may shed significant light on the subtlety of change through time. Likewise, a comparison between the tavern artifacts and data from recent comparative tavern artifact studies (e.g., Rockman and Rothschild 1984) may determine if the assemblage is typical or atypical of an urban tavern site.

These and other questions are the focus of this report. Historical archaeology is almost unique in that it provides very specific, and yet highly generalizing, information; it is also, unfortunately, unique in that it cannot be truly replicated. The physical context of the objects and features-by far their most important attribute--is lost forever once they are dug up. By careful recording and interpretation, however, this context can be well understood, and this understanding can contribute toward a more meaningful interpretation of the lives of the occupants.

Chapter 2: Property Description

The Shields Tavern site (Block 9, Areas G, L and M) lies on the south side of Duke of Gloucester Street, some 300 feet west of the reconstructed Capitol. In 1928, near the beginning of the Restoration, the property was owned by Sophia Wynne Roberts, who made her home in a two-and-a-half story frame building constructed around 1861. Ms. Wynne Roberts, a life tenant on the site after her sale of it to W.A.R. Goodwin, moved in 1952; archaeological excavations were immediately begun in order to facilitate reconstruction of the former tavern (Samford 1985).

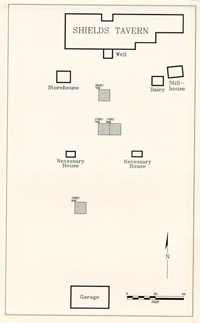

This building was soon reconstructed to its supposed appearance during the period 1708-1714, and given the name "Marot's Ordinary." Six outbuildings and a well were also reconstructed in the back yard. The tavern became a private residence, which it remained until 1985, when the decision was made to convert it to Colonial Williamsburg's fourth operating tavern.

The reconstructed building (Figure 1), which has been altered in the interior but retains its former exterior appearance, is composed of two adjoining hall-and-parlor structures linked by a large central double chimney and a long shed addition on the south. In form it is more representative of mid-rather than early eighteenth-century architectural design (Mark R. Wenger,

Figure 1. Shields tavern

6

personal communication), but it appears that the original 1708 building differed only in structural detail and not significantly in general layout. Less accurate, however, are the reconstructed outbuildings; recent excavations and documentary analysis suggest that there is no evidence for the early dates attributed to the "Stillhouse" and "Dairy," and no evidence at all for the two necessaries. The "Storehouse" and "Stable," however, were probably present at least by the Shields period.

Figure 1. Shields tavern

6

personal communication), but it appears that the original 1708 building differed only in structural detail and not significantly in general layout. Less accurate, however, are the reconstructed outbuildings; recent excavations and documentary analysis suggest that there is no evidence for the early dates attributed to the "Stillhouse" and "Dairy," and no evidence at all for the two necessaries. The "Storehouse" and "Stable," however, were probably present at least by the Shields period.

Figure 2. Backyard prior to excavation, looking south.

Figure 2. Backyard prior to excavation, looking south.

At the beginning of excavation, much of the rest of the back yard was reconstructed as a pleasure garden, which included a grape arbor and a large number of English boxwoods (Figure 2). This area was eventually stripped; after the construction of the underground kitchen that necessitated the project it has been returned to its approximate appearance in the mid Figure 3. Proposed restoration plan for back yard. eighteenth century (see Figure 3).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Like most lots for which records are available, the history of the Shields Tavern property has been extensively researched. In late 1951 Mary Goodwin completed a house history entitled "'Marot's' or 'The English Coffee House,'" which traces the property from 1708 through the nineteenth century. As part of the recent reinterpretive effort, this history has been updated by Patricia Gibbs of the Department of Historical Research (Gibbs 1986a). Most of the documentary information in this report comes from these two sources, along with the carefully-organized database of York County records compiled by Colonial Williamsburg historians.

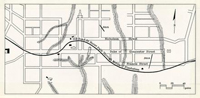

As the evidence from these sources clearly shows, Shields Tavern was well located from the very beginning (Figure 4). Because Duke of Gloucester Street, some ninety-nine feet wide and almost a mile long, was the main street connecting the Capitol with the Wren Building of the College of William and Mary, any property along the way had a significant commercial advantage. This was particularly true of taverns, since convenience and accessibility was a major drawing card.

Williamsburg became the capital of Virginia in 1699, rising out of a small community known as Middle Plantation. Serving as the capital until 1780, Williamsburg was the political and social center of the colony. As the town grew:

Figure 4. Portion of the so-called "College Map" of 1790, showing the location of Shields tavern (shaded).

8

Figure 4. Portion of the so-called "College Map" of 1790, showing the location of Shields tavern (shaded).

8

Taverns were established to feed and house those in town on government business. Lawyers settled here to be close to the General Court. As the century progressed, more and more stores were opened to provide merchandise to out-of-town shoppers .... Carpenters and masons moved to town to build houses and shops. Bakers, tailors, and barbers settled here to serve both visitors and townspeople (Olmert et al. 1985:14).Although the resident population during this period never exceeded around 2000 (about half of them slaves), the town expanded considerably during the twice-yearly meetings of the General Court known as "Public Times." At this time the town's population more than doubled, and tavern keepers, merchants, and craftspersons could expect to do a booming business.

For most of the eighteenth century, the number of taverns in town fluctuated between eight and fourteen (Colonial Williamsburg 1981:3). Most were concentrated along either side of Duke of Gloucester Street, particularly on the eastern side of town close to the Capitol. It was this area that contained some of the most important taverns in the colony: Marot's, Wetherburn's, and the famous Raleigh. The area was also the site of stores, offices, and private residences.

IMMEDIATE SURROUNDINGS1

As the town grew, specific sectors became more or less diversified as shifts in landholding, tenancy, and public life created distinct small sub-communities. In order to better understand the events on the Shields Tavern site, therefore, it is necessary to have a detailed picture of the changing events in the immediately-surrounding area. This discussion is limited--it is focused only on the so-called "Block 9," the block containing the Shields Tavern site--when in fact the site's occupants were daily being affected by events all over town. Nonetheless, it provides at least a partial framework for the evaluation of local events in a wider context.

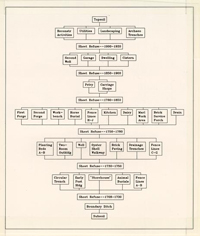

Block 9 was relatively unpopulated until the middle of the eighteenth century (Figure 5), with the predominant property type being private residences. After the initial purchasers--Richard Bland, James Shields I, and William Robertson--received their lots, all presumably built houses within the two years prescribed by the city trustees.

Archaeological and architectural investigations suggest that Shields' and Bland's homes probably fronted on Duke of Gloucester Street, Robertson's on Francis Street.

Shields, a tailor and tavern keeper, had a dwelling house on lot 24 until 1707, when he sold it to William Byrd II of Westover. Eight months later he sold the adjoining lot--25--to tavern keeper Jean Marot. In 1716, Richard Bland also sold his lots, giving lots 20 and 21 to Colonel Nathaniel Harrison. Robertson maintained his property on the eastern side of the block, although twice subdividing it. In 1708, he sold a 40 x 40 foot section adjoining lot 25 to Jean Marot, and in 1718 he sold the entire northeastern part of lots 26 and 27 to a new immigrant from England,

9

Figure 5. Reconstruction of Block 9 (Lots 20-27) for the years 1708, 1714, 1720, and 1736. Dashed lines represent hypothetical locations of buildings based on documentary evidence, solid lines are foundations discovered archaeologically.

10

Dr. John Brown. Brown's lot was identified by Robertson as:

Figure 5. Reconstruction of Block 9 (Lots 20-27) for the years 1708, 1714, 1720, and 1736. Dashed lines represent hypothetical locations of buildings based on documentary evidence, solid lines are foundations discovered archaeologically.

10

Dr. John Brown. Brown's lot was identified by Robertson as:

Beginning at that Corner of Lott 27 which joins on Duke of Gloucester Street & the Capitol Square & running thence ¼ of a degree East Twelve poles thence West ¼ South Two poles Six links to a Stake Standing about four foot from the Corner of the sd Robertsons Milk house Thence North Twelve Degrees five minutes West Eight Poles to the Third post of the Garden pales a little above the Upper Corner of the Barbers Shop Thence West a ¼ South three poles Twenty Two links thence North a ¼ West along Sullivants Pales to his Corner post on the Main Street.. (York County Records, Deeds and Bonds 3:267).

"Sullivants Pales" refers to a fence erected by the occupants of the Shields Tavern site--Jean Marot's widow Anne and her new husband Timothy Sullivant. Brown retained the lots next to the Sullivants until his death, with his widow in 1730 selling a 3968-square-foot area on the northwestern corner of lot 26 to watchmaker John Stott. Stott apparently constructed a dwelling on this parcel.

In 1738 Benjamin Harrison, son of Colonel Nathaniel Harrison, sold lots 20 and 21 to the now-famous tavern keeper Henry Wetherburn. Wetherburn probably first made only his home there, keeping the Raleigh Tavern across the street through 1742, but by 1746 he had moved his tavern to lots 20 and 21 (Gibbs 1968).

At mid-century the block was diversifying rapidly (Figure 6). Merchants Alexander Finnie and James Crosby apparently kept stores on lots 22 and 23, respectively, until 1749, when Crosby sold to Scottish merchants Andrew and Archibald Buchanan & Company:

... Three Lots of Land [22, 23, and 24] containing half an acre in each Lot (upon one of which Lots there is built a Dwelling House & Kitchen upon the Middle Lott is a Storehouse and upon the other Lott there is a Ware house & Stable) .... (York County Records, Deeds 5:393-394).

East of Shields Tavern were two private residences, now owned by "Gent" Nathaniel Walthoe and lawyer John Palmer. Palmer also had a store on his property. To the south, wealthy merchant William Nelson of Yorktown had purchased the former Robertson property and probably rebuilt a new, larger house fronting on Francis Street.

In 1754, a disastrous fire, started in a "back room or counting house joining to a store next Mr. Walthoe's, which was let to a merchant," ravaged the eastern side of the block. This fire is clearly described in the diary of Daniel Fisher, who was living on the Shields Tavern site at the time:

… on Saturday the 24th of April 1754, about 8 in the Evening, I being just got to bed my Daughter alarmed me with the cry of Fire at a neighbor's house, one Mr. Palmer, an Atty; there was our good friend Mr. Walthoe's house only between which and us… between the East end of Mr. Walthoe's house and this in flames, was a void space of about Thirty foot, and the wind directly at west, a strong Gale, so that but from the effects of the Gun Powder [in the store where the fire began] there was no real danger, … but the explosion of the Gun Powder, (the roof then all in a blaze) scattered the firebrands upon Mr. Walthoe's house, already heated or dryed like tinder by the adjacent flames, set his house also instantly in a blaze. Had his house been covered with wet bags or blankets, that would have preserved it, but for more than an hour not a ladder (or other useful implement) could hardly be met with (Pecquet du Bellet 1907:11. 779-780).11

Figure 6. Reconstruction of Block 9 (Lots 20-27) for the years 1740, 1749, 1750, and 1754. Dashed lines represent hypothetical locations of buildings based on documentary evidence, solid lines are foundations discovered archaeologically.

12

The Walthoe and Palmer houses were destroyed, as was the store and a "Jeweller's Shop." Palmer's house was later rebuilt, but Walthoe simply moved to another of his properties in town, selling his part of Lot 26 to Palmer.

Figure 6. Reconstruction of Block 9 (Lots 20-27) for the years 1740, 1749, 1750, and 1754. Dashed lines represent hypothetical locations of buildings based on documentary evidence, solid lines are foundations discovered archaeologically.

12

The Walthoe and Palmer houses were destroyed, as was the store and a "Jeweller's Shop." Palmer's house was later rebuilt, but Walthoe simply moved to another of his properties in town, selling his part of Lot 26 to Palmer.

The western side of the block remained a mixture of residential and commercial properties. In 1759, Henry Wetherburn sold a forty by fifty-six foot piece of lot 20 to merchant James Tarpley, who soon constructed a "new store house." At his death in 1760 Wetherburn also owned a "Tenement in Possession of James Martin Barber," in addition to his by-now well-equipped tavern. Lots 22 and 23 were probably occupied by a merchant, John Carter, while lot 24 was the residence of a widow, Joanna McKenzie, who possibly operated a millinery shop in her home.

The years 1760-1775 saw few major structural changes in the block (Figure 7). Before 1772, and possibly by 1769, barber and wigmaker Edward Charlton was living in a building on the eastern side of lot 22. Two small tenements separated this building from the former Wetherburn's Tavern, now owned and operated by tavern keeper James Southall. One of these was apparently used as Charlton's shop; the other was rented to tailor James Slate in 1774. Tarpley's former property was sold in 1767 to Yorktown merchant Jonathan Pride, who rented it to another merchant, James Hubard, in 1773. The next year, following Hubard's death, the property was rented by jeweler and clockmaker Robert Bruce. Later that same year, however, Bruce moved out and the former dwelling and store were taken over by printer Alexander Purdie, who published the Virginia Gazette from this location. The printer himself lived some six houses down, in the large dwelling on Lot 24.

By 1772, a new tavern, the "King's Arms," had been opened on Lot 23. This large establishment, operated by Jane Vobe, rivaled Robert Anderson's (formerly Wetherburn's) and the Raleigh in terms of size, having some fourteen rooms, four passages, and two porches, along with a kitchen, cellar, laundry, storehouse, shop, and well.

The former Palmer house, east of the Shields Tavern site, had been rented in 1769 by cabinetmaker Benjamin Bucktrout. He apparently left shortly after, as by 1772 the large house was rented to a physician, Dr. John Minson Galt, and a merchant, Beverley Dickson. Much later, in 1787, the property housed a snuff manufactory.

A clear pattern of growth, diversity, and almost constant flux marked this block throughout the eighteenth century. Lots changed hands with relative frequency, tenants came and went, buildings were added, and the spatial configuration of yards and workspaces underwent numerous alterations. Similar patterns are seen on the lots across Duke of Gloucester Street, and indeed throughout the section of town closest to the Capitol.

It can thus be seen that the changes in the character of the Shields Tavern site are reflective of larger changes in the composition of the immediate neighborhood. Very early, Marot's establishment was surrounded by private residences, and the density of structures was very low. Commercial enterprises followed even before mid-century, culminating in the transformation of the block to a densely-packed commercial/

13

Figure 7. Reconstruction of Block 9 (Lots 20-27) for the years 1760, 1772, 1775, and 1790. Dashed lines represent hypothetical locations of buildings based on documentary evidence, solid lines are foundations discovered archaeologically.

14

residential zone by the 1760s. Other taverns on either side of the street competed with James Shields' establishment, and possibly resulted in the squeezing out of tavern keeper Daniel Fisher in the early 1750s. Ironically, several years after Shields Tavern became a tenement, another large tavern, the King's Arms, was opened next door. By the Revolutionary War period, the tenement and industrial facilities established by blacksmith John Draper on the property had become only part of a highly-diversified neighborhood that was home to residences, stores, taverns, and craft shops.

Figure 7. Reconstruction of Block 9 (Lots 20-27) for the years 1760, 1772, 1775, and 1790. Dashed lines represent hypothetical locations of buildings based on documentary evidence, solid lines are foundations discovered archaeologically.

14

residential zone by the 1760s. Other taverns on either side of the street competed with James Shields' establishment, and possibly resulted in the squeezing out of tavern keeper Daniel Fisher in the early 1750s. Ironically, several years after Shields Tavern became a tenement, another large tavern, the King's Arms, was opened next door. By the Revolutionary War period, the tenement and industrial facilities established by blacksmith John Draper on the property had become only part of a highly-diversified neighborhood that was home to residences, stores, taverns, and craft shops.

Chapter 3: The Role of Taverns in Colonial Towns

For most of its history, of course, the Shields Tavern site housed a tavern keeper and his or her family. The eighteenth-century tavern or ordinary-in Virginia the terms were largely interchangeable--was among the most important of public establishments. In the emerging towns, in particular, the tavern provided a social center where "the stranger could learn of the place he was in while the citizen heard news of the outside world"(Rice 1983:67). Most offered food, drink, lodging, and amusements to the men--and they were frequented almost totally by men--who could afford to pay.

Nonetheless, tavern keeping was a precarious business, and very often met with eventual failure. Regulation was fairly strict, and it was necessary for most successful tavern keepers to occasionally venture outside the law. A tavern keeper, cognizant of the various attractions that would entice certain members of the community to visit one's establishment, needed a keen business sense and a realization that profit was not solely dependent on basic services. As one tavern keeper surmised, "[w]e that entertain travelers must strive to oblige everybody, for it is our dayly bread" (Rice 1983:49).

The social and economic importance of the tavern in colonial American society was such that the colonial governments stipulated that such facilities be established in every town. As significant in their own way as churches and courthouses, they sprang up anywhere and everywhere, though most commonly near the town's commercial center. Their function was far more than commercial, however; as Rockman and Rothschild state, "[a]s public meeting places, taverns constituted the only large public building which could serve as places for groups of people to meet both formally and informally for secular purposes" (1984:113).

Taverns were usually divided into public space, which was strictly regulated, and less well-regulated private space, as well as the accommodations for the tavern keeper's family. It was the private space that often furnished the tavern keeper with his or her greatest profits. It was common during the second half of the eighteenth century for larger taverns to offer private club facilities to the various fraternal organizations that were often found in an urban center (Gibbs 1968; Rice 1983). These private rooms permitted gentlemen to converse freely, usually accompanied by heavy smoking, drinking, and gambling. Private rooms could also be rented out to the wealthy individual traveler or his party, almost always at a relatively high price.

Separated from the private chambers in a tavern, and made available to the general populace, were the public rooms. Similar amusements were available, but meals were offered at a set rate, served at an established time, and usually consisted of simpler fare. The prices of individual drinks as well as meals had to be posted in the most public room of the facility, and rates could not exceed the limits determined annually by the local court. For example, on March 24, 1709, the following 16 rates were established by the York County Court:

(York County Records, Orders, Wills 15:6)

This Court do Sett & Rate for [£.s.d.] Each Dyet 0. 1. Lodging for Each person 0.-. 7½ Stable Room & ffodder sufficient for Each Horse per Night 0.-. 7½ Stable Room & ffodder Sufficient for Each Horse 24 Hour's 0. -.11½ Each Gallon of Corn 0.-. 7½ Wine of Virginia Produce per Quart 0. 5. - Canary & Sherry per Quart 0. 4. - Red & White Lisbon per Quart 0. 3. 1½ Western Island Wines per Quart 0. 1.10½ French Brandy per Quart 0. 4. - French Brandy Punch or French Brandy Flip per Quart 0. 1.3 Rum & Virginia Brandy per Quart 0. 2. - Rum Punch & Rum fflip per Quart -. -. 7½ Virginia Beer & Cyder per Quart -. 0. 3¾ Pensilvania Beer per Quart -. -. 6 English Beer per Quart -. 1. -

Catering to the private clubs, while at the same time entertaining the general public, enabled the tavern keeper to attract clientele of various tastes. This was further accomplished through their promotion of, and participation in, a variety of commercial activities, many of which were held at their establishments. Estate auctions, consignment sales, lectures, and exhibits were but a few of the events intended to attract the curious and provide the tavern keeper with the opportunity to sell food and drink. At the very least, such commercial ventures helped establish the facility as a focal point of social gathering in the community; depending on the convenience of its location and the quality of services, they may also have attracted new customers.

Colonial laws to regulate the business practices of the tavern keeper were established as early as the first half of the seventeenth century, as were those to prevent unqualified individuals from legally entering the profession. Licenses were required, although there is some indication that in Virginia they were not always regularly renewed (Gibbs 1968; Yoder 1979). Several considerations were taken into account when the justices of a local court reviewed an applicant's petition for a tavern license (Bragdon 1981). These included the overall financial status of the petitioner, the proposed location of the tavern, and its proximity to previously-established public houses. The court also required that the would-be tavern keeper be of good moral standing and competent to perform his or her duties. In Virginia, a bond of ten thousand pounds of tobacco or fifty pounds current money was required, along with a license fee of thirty-five shillings or fifty pounds of tobacco (Gibbs 1968:17).

Tavern keeping was "a middling occupation which provided a modest opportunity for an individual, and a steadier income than agriculture or other labor would have permitted" (Rice 1983:31). Few tavern keepers, even in urban areas, were able to make a living solely from this profession, and in fact the business experience and ready capital necessary to invest in a tavern was usually obtained from a secondary trade held by the petitioner. In late seventeenth-century Brookline, Massachusetts, for example, Erosamon Drew "apparently capitalized upon the success of his sawmill by turning his home into a tavern" (Beaudry 1984:33). Likewise, in 1745, William Reynolds of Annapolis, Maryland supplemented the income from his prosperous hat maker's shop with that from a tavern which he operated out of the same facility (Historic 17 Annapolis Inc. 1979). For the less prosperous individual with little business experience, having influence with a member of the court sometimes allowed the petitioner to circumvent the somewhat stringent requirements of the licensing system. Daniel Fisher, an unsuccessful tavern-keeper in Williamsburg during the mid-eighteenth century, complained of this practice and noted that one tavern keeper even "obtained a lysence at the county court whereof he is himself a member" (Rice 1983:64).

Abuse of the licensing system was also practiced by those who directly benefited from the collection of licensing fees:

These monies, in the case of the royal governorships, were the entitlement of the governors and/or the colony's proprietors. Greed could have been a major motivation behind the overall increase in the number of tavern licenses after the first decades of the 18th century (Rice 1983:64).

Although tavern regulations were not always strictly enforced, they were intended to prevent unscrupulous tavern keepers from overcharging their patrons, while also protecting the tavern keeper from non-payment by derelict customers. In 1638, the Virginia General Assembly:

limited the prices that a tavern keeper could charge for a meal or a gallon of beer to six pounds of tobacco or eighteen pence. By the next year, 1639, commissions were being issued by the governor to individual tavern keepers. These commis-ion specified that no unlawful games or disorders should take place at taverns (Gibbs 1968:14).

Amendments were added to seventeenth-century tavern legislation during the first decade of the eighteenth century, prohibiting unlawful gaming, drunkenness, and retailing liquor without a license (Gibbs 1968). They also required the use of sealed weights and measures to assure the customer that he was sold the proper amount.

DRINKING, LODGING, AND GAMBLING

Certainly, the consumption of alcoholic beverages was an important part of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century life. Depictions of colonial taverns almost always show guests holding wine glasses or tankards of ale (Figure 8). In order to protect the business interests of other members of the community, however, tavern keepers were prohibited by law from selling alcoholic beverages to blacks, servants, Indians, apprentices, students and seamen, unless permitted to do so by their masters or ships' captains. The prohibition was ostensibly due to the adverse impact of strong drink on the performance of their duties and, for seamen especially, the reckless spending of wages intended to support their families. Tavern keepers in Williamsburg, in addition, were not permitted to sell liquor to workmen constructing the Capitol, as members of the Assembly felt that alcohol would diminish the quantity and quality of their work (Gibbs 1968). These prohibitions were only a slight inconvenience, however, as there are numerous well-documented instances of illegal but conspicuous possession and consumption.

These same laws stipulated not only to whom alcohol could not be sold, but also the amount of credit which the

18

Figure 8. English tavern scene, circa 1750-1775.

tavern keeper could extend to "people of modest circumstance 'who were not master of two servants or… worth fifty pounds sterling'" (Yoder 1979:265). Although such a restriction was thought by some to be unjust, it served to protect tavern businesses. Tavern keepers were sometimes unable to collect for the services they rendered; hence, they frequently could not meet their own financial obligations. To avoid economic ruin, it was common for desperate tavern keepers to make public their need to collect payments for unsettled accounts (Gibbs 1968; Rice 1983). In Williamsburg, however, this restriction was removed during the sessions of the General Court or the House of Burgesses (Yoder 1979).

Figure 8. English tavern scene, circa 1750-1775.

tavern keeper could extend to "people of modest circumstance 'who were not master of two servants or… worth fifty pounds sterling'" (Yoder 1979:265). Although such a restriction was thought by some to be unjust, it served to protect tavern businesses. Tavern keepers were sometimes unable to collect for the services they rendered; hence, they frequently could not meet their own financial obligations. To avoid economic ruin, it was common for desperate tavern keepers to make public their need to collect payments for unsettled accounts (Gibbs 1968; Rice 1983). In Williamsburg, however, this restriction was removed during the sessions of the General Court or the House of Burgesses (Yoder 1979).

Like alcohol, gambling in principle was restricted to the wealthy:

In Virginia gambling was considered a gentleman's privilege, forbidden to members of the working class--apprentices, craftsmen, laborers, seamen, and servants--since gambling caused them to neglect their work. A law passed in 1740 imposed a ten-pound fine on an innkeeper who permitted play at any game of cards or dice, except backgammon (Gibbs 1968:24).

Eight years later an amendment was added to the legislation which set the same fines for those convicted of the violation, but increased the number of games that were permissible to include billiards, bowls, chess, and draughts. Even this softening of the law was ineffective, however, as gambling was so prevalent in taverns during the second half of the eighteenth century that enforcement was virtually impossible. A French visitor to Virginia in 1765, observing 19 the activities of certain members of the Williamsburg community, commented:

In the daytime… hurrying back and forwards from the capitall to the taverns and at night, Carousing and drinking in one chamber and box and dice in another which continues till morning Commonly. There is not a publick house in Virginia but have their tables all battered with the boxes … (Rice 1983:112).

Games were essential elements in the tavern keeper's establishment. As with the provision of good food and abundant drink, these forms of entertainment served to bring people together and encouraged social interaction. Of course, such interaction was hard to avoid; typically, even the wealthy slept communally in the same room and even in the same bed. Individualism was overshadowed by group activities, and privacy was difficult to achieve. Even as late as the 1790s, the German traveler Johann David Schoepf found that:

travellers, almost anywhere in America must renounce the pleasure of withdrawing apart, (for their own convenience or their own affairs), from the noisy, disturbing, or curious crowd, unless it may be, that staying at one place for some time, a private apartment is to be rented (Morrison 1968:II:64).

Naturally, close interaction encouraged conversation, in a culture that was in any case more inclined toward oral than written communication. As one anonymous eighteenth-Century tavern patron surmised:

To avoid conversation is to Act against the Intention of nature... to live then as men we must confer with men; conversation must be one of the greatest pleasures of life (Rice 1983:79).

This was especially true within the tavern. While certain tavern-like establishments offered less exuberant and somewhat more reserved atmospheres, it has been stated of the tavern "that every person coming in must be thoroughly answered, since there is no place apart, where one may avoid curiosity or occupy himself with his own affairs" (Rice 1983:79). Hence, conversation accompanied by considerable drinking and gaming established a social bond between individuals that allowed an escape from mundane everyday existence and the opportunity to be better informed of the events beyond the confines of their community (Rice 1983).

TAVERN LANDSCAPES

One of the most complete descriptions of the landscape surrounding a tavern comes from a property only a few doors away. A thorough excavation of Henry Wetherburn's yard in 1965 (I. Noël Hume 1969a) disclosed several outbuildings, including a kitchen/ laundry, smokehouse, and dairy, along with evidence of an extensive network of walkways in the yard. Remains found in an abandoned well suggest that fruit trees were growing behind the tavern as well. The discovery of a famous group of cherry-filled glass bottles buried in the soil are only one indication that the yard was used for all sorts of purposes, and was truly a "resource" to be exploited and modified.

For those taverns that have not been archaeologically investigated, or have been investigated less thoroughly, it is difficult to find particular reference to the surrounding landscape. Suggestive, however, are references such as the 20 advertisements for the hire of horses and carts (Gibbs 1968:124), indicating that a stable and small pasture were often present nearby. It would be fairly easy to believe that kitchen gardens and perhaps chicken coops were common. But the exact form of the yard can only be understood through careful archaeology, and it is in this area that archaeology can make one of its greatest contributions to colonial tavern studies.

FOOD SERVICE

Rice (1983:86) states that "although the emphasis on cuisine was secondary [to the provision of drink], it was nevertheless an important part of the customer's tavern experience." By law, Virginia taverns were required to offer regular meals, at a cost of around a shilling (Gibbs 1968:66). Whether the experience was favorable, however, was dependent not only on the quality and type of food served, but also on the expectations of the patron. Generally, travelers anticipated entertainment standards to be low, and held little hope for an elaborate meal. Customers, however, expected more from urban taverns than from rural ones. For example, Daniel Fisher, in his journey from Virginia to Philadelphia in 1755, expected at one rural tavern to be served "anything that was ready in the house." He was not disappointed, as he got "an English Hoe Cake, made out of wheat flour, with butter, accompanied by tea and sugar" (Rice 1983:86). The variety of meals offered was hardly staggering, as Nicholas Cresswell, traveling through Virginia in 1774, wrote despairingly:

Have had either bacon or chickens every meal since I came into this country. If I continue in this way, shall be grown over with Bristles or feathers (McVeagh 1924:20).

Most facilities made available an "ordinary" or "common table" meal that was generally similar to its rural tavern counterpart: "The foods were generally hearty, easily available, and often simply prepared by boiling or stewing" (Howard 1985:2). In addition, urban tavern keepers frequently made available more elaborate meals, with a greater variety of dishes, for special clients. The wealthy planter and gentleman William Byrd II, for instance, often dined with friends and guests at Jean Marot's tavern in Williamsburg during the early part of the eighteenth century, and some decades later at Henry Wetherburn's tavern in the same area.

There were not likely to be great variations in the common fare served to the general public, which was most likely bland, easily prepared, and easily preserved for later use. Where the differences were more likely to show up was in the "fancy" fare served to wealthy guests--the very area that provided the tavern keeper with his or her greatest potential source of profit.

Market accounts in 1785 for Thomas Allen's tavern in New London, Connecticut demonstrate:

the variety of foodstuffs available in agrarian America, the types of food used, the kinds of dishes prepared and served at the City Coffee House and other taverns in urbanized areas... Between January 9 and March 16, 1774, Allen purchased locally, and subsequently served to his customers, beef once, veal seven times, fowl and turkey five times, mutton twice, and lobsters, salmon, eels, oysters, duck, and 21 other fish caught in nearby Long Island Sound at least once. He kept stores of gammons (smoked ham and bacon), smoked and pickled tongue and beef, salt prk, crackers, butter, coffee, apples, and sugar on hand... In addition, Allen served bread and a potpourri of vegetables: potatoes, carrots, peas, beans, beets, onions, cabbages, turnips, squashes, and cucumbers for pickling. He bought several types of English cheeses and imported lemons and limes for punch (Rice 1983:86).

The food and drink provided by a tavern keeper was the heart of his operation, and, as with his other services (i.e., overnight accommodations, gaming, and auctions), were offered in a facility in which social interaction was not only encouraged but expected. Travelers who frequented rural taverns often joined the tavern keeper and his family at their table to share the meal. Although many urban taverns had both public and private dining areas by the end of the first quarter of the eighteenth century, customers often dined communally well into the century, as described by Henry Wansey:

I [W]e were shewn into a room where we found a long table covered with dishes, and plates and close seating arrangements for twenty persons.

With such arrangements, Wansey concluded that:

there is no shyness of conversation... as at an English table. People of different countries and languages mix together, converse as familiarly as old acquaintances(Rice 1983:88).

Chapter 4: Previous Archaeology

The first excavations on the Shields Tavern site took place in July 1951 and March 1952. Under the supervision of Foundation archaeological draftsman James M. Knight, these excavations were intended to locate, expose, and record all eighteenth-century foundations on the property in preparation for the reconstruction of the tavern and its outbuildings. Extensive excavation was necessary, since no eighteenth-century structures had survived.

Knight followed an excavation, strategy and methods which had been in use in Williamsburg during the previous twenty years:

The method, known as cross-trenching, involved the digging of parallel trenches a shovel blade in width and a shovel length apart, and throwing the dirt up onto the unexcavated space between them. Because the colonial buildings of Williamsburg were set out parallel to the streets, the trenches were dug at a 45-degree angle to the streets on the theory that such cuts would most quickly locate foundations running at right angles to each other(I. Noël Hume 1975:72).

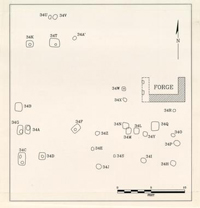

The excavation of no fewer than sixteen cross-trenches across the Marot's Ordinary property located six foundations, two of which were characterized only by robbed brickwork (Figure 9). The examination of the foundations' dimensions, brick size, interior wall

Figure 9. Archaeological features discovered by James M. Knight in 1951-52.

24

locations, and mortar type guided field interpretation of the various sequences of building construction and possible building function. Rather than actual dates, relative "periods of construction" were assigned to the foundations. Hence, field interpretations of building sequences were far from conclusive, and the eventual reconstruction was based largely on documentary evidence.

Figure 9. Archaeological features discovered by James M. Knight in 1951-52.

24

locations, and mortar type guided field interpretation of the various sequences of building construction and possible building function. Rather than actual dates, relative "periods of construction" were assigned to the foundations. Hence, field interpretations of building sequences were far from conclusive, and the eventual reconstruction was based largely on documentary evidence.

The network of foundations upon which the tavern was reconstructed fronted the south side of Duke of Gloucester Street. Knight's excavations located two large, attached building foundations skirted on the south and east by later additions (Figures 10 and 11). The westernmost of the two principal foundations was assigned to the earliest period of construction. This building was followed by the "2nd Period Construction" of a somewhat larger structure, joined to the east end of the first by what may have been a double chimney. Indications are that beneath this second building was a full cellar, with a large fireplace and hearth at its eastern end. Located on the south side of the two joined buildings was another foundation, denoted "3rd Period Construction"--remains of a narrow, lengthy addition. The construction of a small rectangular addition onto the eastern end of the building represented the final episode of eighteenth-century construction.

Figure 10. 195l-52 excavation showing cellar of east wing and long shed addition, looking west.

Figure 10. 195l-52 excavation showing cellar of east wing and long shed addition, looking west.

Figure 11. 1951-52 excavation showing cellar of east wing, looking north.

Figure 11. 1951-52 excavation showing cellar of east wing, looking north.

Twenty-nine feet south of the easternmost addition lay a complex of outbuilding foundations (Figure 12). Two of these were eventually reconstructed to the earliest period as a supposed "stillhouse" and "dairy." A third foundation, with a substantial chimney at its eastern end, was dated to the nineteenth century and was not reconstructed. Located twenty feet south of the west end of the tavern, a storehouse was reconstructed over a robbed brick foundation which enclosed remnants of a brick-paved floor. It should be noted, however, that while three of these dependencies were reconstructed for the earliest tavern period on the site, a careful review of documentary evidence and recent archaeological results suggest that the reconstruction of two of the outbuildings--the stillhouse and dairy-is highly suspect.

Located north of the reconstructed outbuildings, and abutting the foundation on the immediate south side of the tavern, Knight discovered the intact brick lining of a well. The well shaft, constructed of regular building brick as opposed to more stable wedge-shaped well brick, had a diameter of three feet, and was covered with a modern well head. It is not clear whether the well was excavated at that time; in any case, partial re-excavation in 1986 revealed that it was filled with early twentieth century debris to a depth of at least sixteen feet. Nonetheless, based on the general pattern of brickwork, it was 26 reconstructed for the Early Tavern period.

Figure 12. Outbuildings discovered in 1951-52 excavation, looking southwest.

Figure 12. Outbuildings discovered in 1951-52 excavation, looking southwest.

In addition to locating numerous foundations on the property, a huge unprovenienced assemblage of ceramic, glass, metal, and bone artifacts was recovered from the cross-trenching and subsequent excavations. While this assemblage has great research value, the techniques of its recovery render it virtually useless in contributing to the reconstruction of particular cultural sequences on the property. The interpretive constraints created by this excavation technique also hindered the refinement of artifact dates in the laboratory. As stated by Moreau B. C. Chambers in the Marot's Ordinary Archaeological Laboratory Report (1955:34), "while all these [iron objects] are presumed to be Eighteenth Century types, it cannot be clearly proved that some may not have been made during the succeeding years that this site was occupied." Clearly, artifact provenience on the site was thought to be extraneous to the goal of architectural reconstruction, and of no significance in dating episodes of construction on the site. In short, archaeology in Williamsburg during the early years of reconstruction was simply a "tool of the architectural restorer," despite utilizing an archaeological record vastly more complex than perceived at the time (I. Noël Hume 1975).

In December 1957, an adjacent property on the west, the Coke Office 27 lot, was cross-trenched. Although documentary evidence indicates that it was part of the Shields Tavern property during the eighteenth century, the lot had been administered separately on the basis of records showing that it belonged to the occupant of Lot 24, John Coke, around 1809. Cross-trenching under the direction of James Knight on this property yielded numerous eighteenth-century features associated principally with John Draper's occupation of the property between 1769 and 1780. The features were subsequently investigated and mapped by Foundation Archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume (Figure 13). Several postholes and an anvil stump hole were recorded immediately adjacent to a "chimney foundation." The excavation of three undisturbed layers within the interior of the brickwork dated the feature to the third quarter of the eighteenth century. The presence of coal, iron, and slag within the bottom two layers, and similar industrial waste material from surrounding features, indicated that the complex was related to a late eighteenth-century forge operation (I. Noël Hume 1958). No tavern-period features, however, were identified on this parcel.

Figure 13. Archaeological features discovered on the Coke Office lot in 1957-58.

Figure 13. Archaeological features discovered on the Coke Office lot in 1957-58.

Chapter 5: Methods

FIELD METHODS,

by Thomas F. Higgins III and David F. Muraca

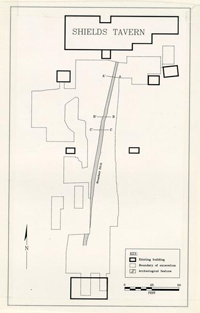

The archaeological investigation of the Shields Tavern property began on August 13, 1985 and was completed on July 1, 1986. Prior to the commencement of the investigation, an archaeological briefing was prepared by staff archaeologist Patricia Samford (1985), based on plan drawings submitted to the Department of Archaeological Research by the Department of Architecture and Engineering. These plans, detailing the area on the property to be impacted by construction of the underground kitchen, indicated that construction of this facility would entail machine removal of all soil in the back yard to a depth of eighteen to twenty feet below modern grade. This would obviously result in drastic alteration to the landscape and would eliminate all traces of previous cultural activity dating to the colonial and post-colonial periods. Because of the rich documentary record for the early occupation of the site, and the inadequacy of previous archaeology, a thorough archaeological excavation was deemed essential. Because funds were limited, an excavation strategy relying upon salvage techniques was adopted, with some areas machine-stripped or shovel-scraped, but others carefully hand-excavated in order to unravel the complex stratigraphic sequences on the most sensitive areas of the site.

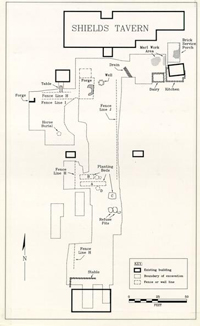

The excavation strategy was in part guided by the landscape of the back yard. In addition to the tavern, there were six standing outbuildings--a stillhouse, dairy, storehouse, stable, and two necessaries. All had been reconstructed, destroying in the process most or all of the archaeological evidence in the vicinity of their foundations. Other recent modifications include the creation of a pleasure garden containing mature English boxwoods, a grape arbor, and numerous other plantings. A large brick service porch with connecting walkways was present on the immediate south side of the tavern, while reconstructed fences separated the main portions of the yard.

Subsequent removal of all plantings, brickwork, and fences permitted total site investigation, with the exception of the disturbed areas around the standing buildings. A grid system (Figure 14) with designated ten-foot markers was oriented north and east over the property, with an arbitrary datum point (a length of steel reinforcing bar) placed on Francis Street. A large paving stone at the base of the porch steps behind the southeastern end of the tavern, 85.90 feet above mean sea level, served as a benchmark for the site. This benchmark was established from a point of known elevation on Duke of Gloucester Street.

The earliest phase involved the excavation of three 10 x 10-foot test units in various parts of the yard, at 200N/70E, 170N/70E, and 10ON/50E (Figure 15). The excavation of these test units disclosed typical soil types, permitted a general stratigraphic sequence to be drawn up, and suggested some areas of stratigraphic complexity that would have to be carefully investigated.

30

Figure 14. Excavation grid superimposed upon the Shields Tavern site.

31

Figure 14. Excavation grid superimposed upon the Shields Tavern site.

31

Figure 15. Initial excavation units.

32

Not surprisingly, the units on the north side of the transect, nearest the tavern, yielded the most complex stratigraphic sequences.

Figure 15. Initial excavation units.

32

Not surprisingly, the units on the north side of the transect, nearest the tavern, yielded the most complex stratigraphic sequences.

Based on the results of this initial testing, several other 10 x 10-foot units were opened up. Because the D.A.R. uses a method known as "open-area" or "block" excavation, in which large sections of the site are excavated simultaneously, these units were selected on the basis of information discovered in adjoining units. Eventually, however, the entire yard, up to the limits of the potential impact area, was exposed.

Following the recording system utilized by the Department of Archaeological Research, individual layers and features found within ten-foot units were assigned a unique provenience or "context" number. The location and extent of each context was recorded on a standard form (Figure 16) along with information about its soil type, degree of disturbance, and general composition. Prior to excavation, each layer or feature was drawn in plan and photographed. A probable date and function was determined from the nature of the context and the age of the layers or features sealing it, thus dictating the excavation strategy. Very late or highly disturbed layers and features were considered of minimal significance and were excavated by the most expedient means. Modern topsoil, for instance, was simply shoveled or graded off.

Features and layers relating to the eighteenth-century occupation of the site were excavated more thoroughly. They were hand-troweled, and all soil deposits were screened through one-quarter inch wire mesh. Some of the most significant features were water screened through one-sixteenth inch window mesh for more complete recovery. All features were sectioned, and section drawings were made of the exposed profile. Layers were mapped using a series of balks or intact unit walls, most of which were later removed. Vertical control on the site was maintained with a level, taking elevations prior to and following the excavation of every feature and layer.